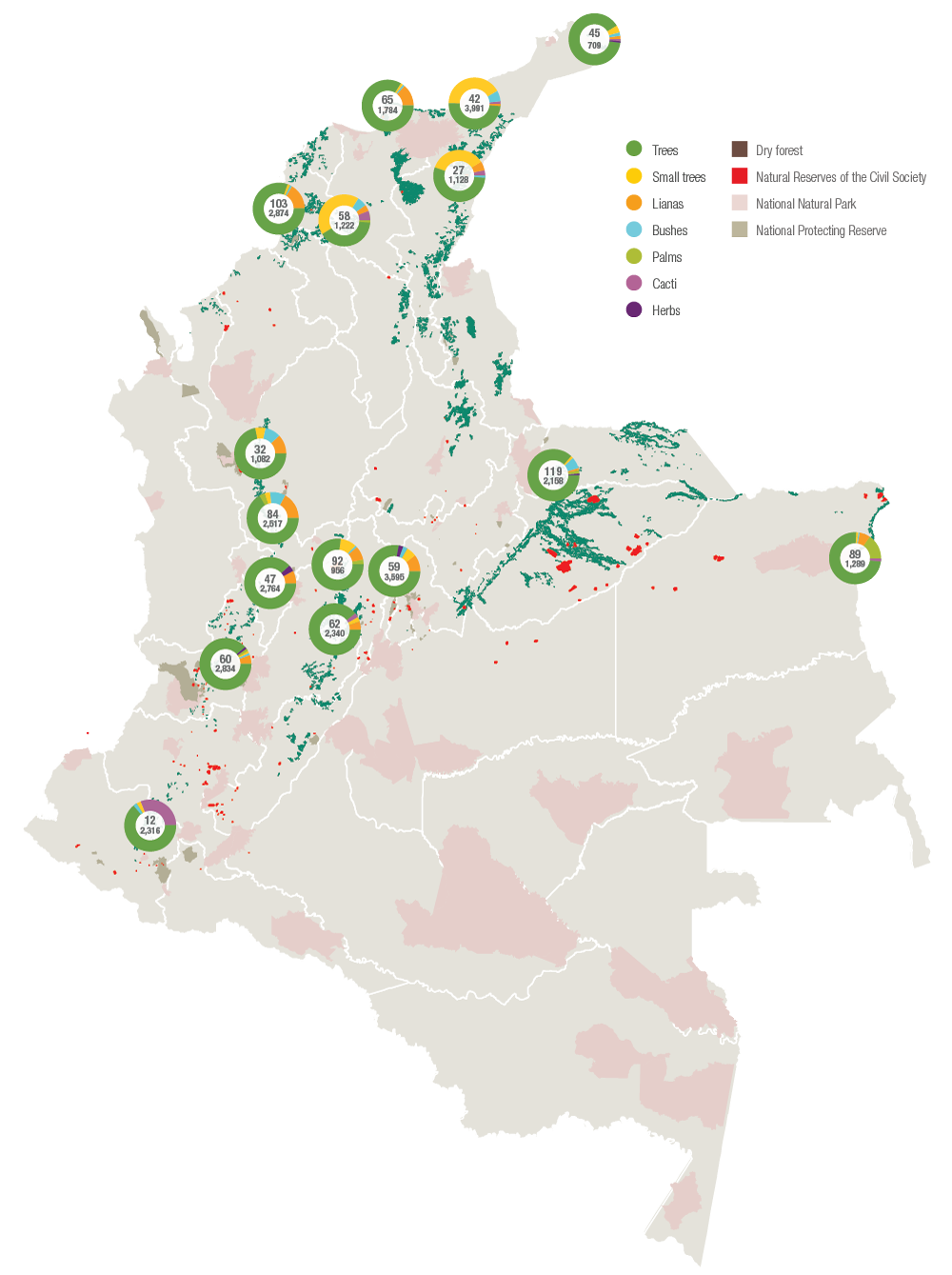

Permanent plots for monitoring dry forest vegetation

Although species diversity varies considerably between regions according to climatic, edaphic, and transformation factors, evidently plots are grouped by region according to their floral composition. The sites selected for the location of the plots represent the least fragmented zones of the five subregions containing dry forest in Colombia. It is still necessary to increase the points of monitoring despite each plot being characteristic of the location and region.

In the Neotropics, dry forests are regarded as ecosystems with high priority for conservation1. Some species inhabit exclusively this ecosystem, resisting high temperatures and marked water restrictions during great part of the year 1,2. Yet the areas that contain dry forests have also supported large human settlements, creating a long history of transformation and loss of biodiversity1,3.

Alarmed by the threats that affect dry forests in Colombia4 and the lack of knowledge about their dynamics and functioning5,6, regional investigators started a national strategy for monitoring the vegetation of dry forests (BSTCol) in 2013. The goal of this initiative is to generate scientific data that may be useful for the integrated management of the ecosystem, especially in the current situation of change and complex socioecological scenarios it faces7.

These monitoring efforts contribute with high quality information that must be the base for decision making in terms od dry forest conservation. Consequently, it is considered that permanent monitoring of vegetation will account for a systematic process of obtaining and analyzing data that will not only explore trends in changes of attributes proper to the species and plant communities in time, but also allow for evaluating the effects different conservation strategies in Colombia have on the integrated management of its biodiversity.

Up to now, based on the analysis of recorded information for the first group of data obtained, 623 species of plants (33,559 individuals), including trees, bushes, palms, lianas, and cacti, have been monitored in all plots (62±29 species/ha). When overlapping the plots with the Sistema Nacional de Áreas Protegidas (National System of Protected Areas, Sinap for its initials in Spanish), it was found that both the areas with strict protection and private conservation initiatives shelter a greater number of species than the forests without management efforts. In Natural National Parks and Regional Parks there are approximately 72 species/ha, in Private Reserves of the Civil Society around 74 species/ha, and in private buildings 51 species/ha.

Nevertheless, there is a high floral exclusiveness and unity in each monitored site and most regions contain endemic species. These facts highlight the importance of Sinap in the integrated management of biodiversity in dry forests and the need of proposing alternative conservation plans for plants in those private areas that currently lack a management strategy based on the integration to productive landscapes in each site.

Even though this initiative is still in its preliminary phase, in the future conservation needs derived from the analysis of plant dynamics, functioning, and response capacities in the face of transformation may be determined thanks to permanent monitoring.

Scientific name: Oxandra espintana

Individuals: 1,222

Critically endangered

Red BST-Col is a monitoring and research initiative for dry forests in Colombia. More than 20 institutions and 40 researchers participate in the regions where this ecosystem is distributed.

Frequent species in monitoring plots

Dry forest representatives

Glassy wood

Scientific name: Astronium graveolens

Plots: 13

Individuals: 844

Distribution: Up to 1,300 m.a.s.l.

View in SiB Colombia

Gumbolimbo

Scientific name: Bursera simaruba

Plots 10

Individuals: 152

Distribution: Up to 1,300 m.a.s.l.

View in SiB Colombia

Monitored forests present high values of floral exclusivity. Close to 72 % of species of one locality were not reported in another.

Each plot is characterized by a great uniformity of plants. Only 5 % of the species are present in more than three localities.

Total number of individuals and species monitored per group of plants

With the obtained data of mortality, recruitment, and growth, the understanding about ecological dynamics and response capacities in the face of drivers of change, especially those related to climatic variability, may be improved.

Interact with graph variables to view number of individuals per group

Monitored endemic species with greatest abundance of individuals

Coya colorado

Scientific name: Trichilia oligofoliolata

Individuals: 1,952

Endemic species of the valley of the Magdalena River

View in SiB Colombia

Coya blanco

Scientific name: Trichilia carinata

Individuals 493

Endemic species of the Magdalena River Valley

View in SiB Colombia

The sites selected for the location of the plots represent the least fragmented zones of the five subregions containing dry forest in Colombia.

Distribution of endemic species by type of governance

4,817 individuals of 13 endemic plant species are being monitored. In the region of the Magdalena River Valley the greatest number (5) is present, two of which have a distribution restricted to the dry forests of the North of Tolima, making it necessary to strengthen conservation actions in these areas.

2. Civil Society Reserves

3. Private buildings

Number of endemic species per hectare

Percentage of endemic species

Select parts of the graph to view related data

PDF version

PDF version Methods (in Spanish)

Methods (in Spanish) References

References Share

Share